How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love My Queer Characters

Today’s blog post comes to us from Sam Cameron. Sam (she/her) is an Author Accelerator certified book coach specializing in kid lit. If you want to know more about LGBTQ+ characters in your kids’ books, you can hear Sam talk about it on Episode 18 of the Coaching KidLit Podcast. You can also take Sam’s free quiz: Is my manuscript LGBTQ+ Inclusive?

Sam Cameron (she/her)

Kid Lit Book Coach

A few months after my sixteenth birthday, I suddenly realized that I had never read any books with a gay protagonist. Instead of searching for such a book, I decided to write it myself. I tinkered with this project in secret. I knew that anyone who read the story would have questions about my sexual orientation and since I was (mostly) closeted, my characters had to stay in there with me.

I am bisexual. I figured this out when I was fifteen, but chose not to tell many people, including my parents. They are warm, loving, accepting people, but it was hard enough for me to talk to them about my feelings for boys, never mind add to that conversation, “oh by the way, I might also like girls?” So, I decided I would only tell them if it became relevant.

It seemed like it never would be relevant. My life followed an unexpectedly heteronormative trajectory. When I was twenty-four, I married my best friend who – at the time – presented as male. We looked like a cis-hetero couple. It felt that way from inside the marriage too.

It was during this part of my life that queer* characters disappeared from my work.

This was in the early days of #ownvoices. I realized that if I published a book with queer heroes, that I would have to talk about my sexuality. In public. With strangers.

I still hadn’t told my family!

Don’t get me wrong. I think it is important for writers and publishers to carefully consider how marginalized communities are represented and who is getting to tell those stories. (In fact, I wrote about it here.) That said, the orthodoxy of #ownvoices can be a double-edged sword for writers who are closeted or questioning. On the one hand, it is important to elevate stories written by queer authors. On the other, if we insist that only openly queer authors can write legitimate representations, then the folks who might be closeted, questioning, or just not wanting to use a label may feel pressured to come out or not write these kinds of stories at all.

I did not want readers to publicly debate my sexual orientation the way they had for Becky Albertalli. So, despite wanting to explore my queer identity in my fiction, I chose not to. It was safer to pass as straight. And anyway, like a lot of bi people who have different-sex partners, I didn’t feel “queer enough.” I might have been attracted to women, but since I’d never actually dated one, what did I even know?

And then the pandemic came. Like everyone else, my world turned upside down. One of the more peculiar gifts of COVID-19 was that my spouse came out as transgender.

Suddenly, I was a woman with a wife.

My bisexuality had become both noticeable and “relevant.” Despite this unexpected coming out, it took some time for queer characters to make it back to centerstage of my writing. I needed some time to mourn the loss of our cis-hetero privilege and adapt to a new vision of our future. (The first decade of our relationship was wonderful, but I have to say, I don’t miss heteronormativity!) I needed some time to connect with queer community and figure out what the heck it even meant to be out and proud.

It took about a year and a half after my wife’s coming out before I committed to writing a queer protagonist. There were three things that made it feel not only possible, but crucial.

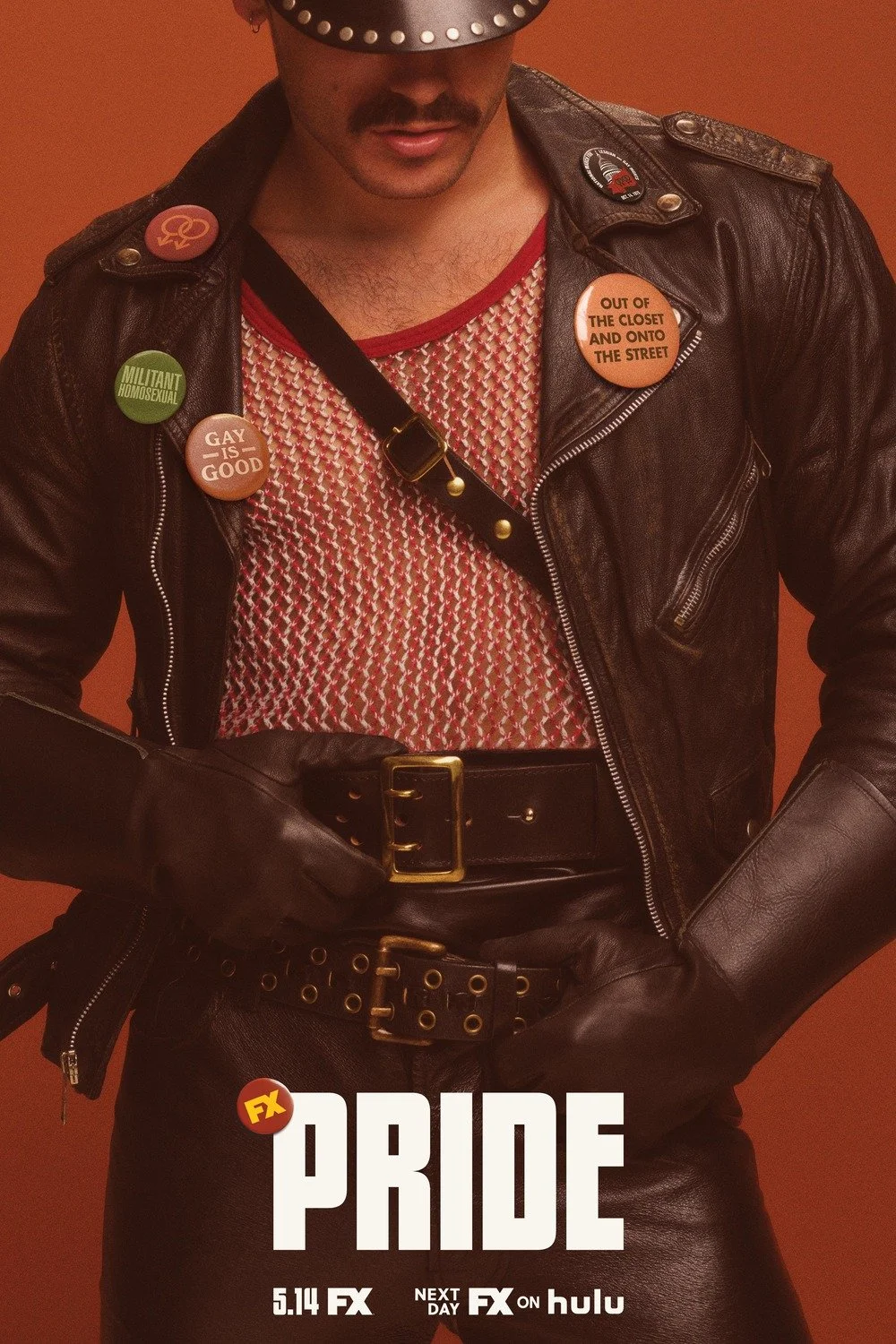

First, I watched the FX docuseries Pride.

In my life outside of writing and coaching, I am a high school history teacher. I have an above-average understanding of U.S. history, and yet, this documentary shed light on history that I – fully thirty years old – had never heard in my life. Seeing the history of the U.S. from World War II to the present recast from a queer perspective made me feel connected to my bisexual identity in a way I never had before. It made me want to plant my flag.

Second, I started reading books about queer heroes written by queer authors.

There are A LOT more of these around than when I was sixteen. Just like I had shied away from writing about queer characters, I had also avoided reading about them while I was passing as straight. I was worried what people would think – especially my still closeted and ostensibly cis/ straight spouse, even though she already knew I was bi.

Reading these books, just like watching Pride, I saw myself reflected in a way I never had before. There were other people – a lot of other people – who felt the way I did.

Third, and most importantly, I started to be open about my identity with my students.

I casually mentioned having a wife, just like I used to casually mention having a husband. I talked about my experiences of figuring out that I was bi and of my wife’s experiences of figuring out that she was trans. I started teaching more queer history. I felt so much more expansive, so much more seen after I revealed this side of myself. But it wasn’t how it made me feel that mattered.

It was what it meant to my students.

Queer and questioning students have told me how “cool” it is to have an openly queer teacher. Some have come to me seeking advice or wanting to talk, because I am the only queer adult they know. I was surprised by how meaningful it has been for these kids who live in an affluent, liberal, and accepting area. But it shouldn’t have surprised me. I know how meaningful it would have been to me when I was their age.

My students’ reactions have also reenergized me to write for the sixteen-year-old I once was. This is the audience I’m writing for: teens. Even though they have an ocean of books about queer identity compared to what I had when I was their age, they still crave these stories.

And so, I’m not just going to plant my flag.

I’m going to wave it.

*Queer is a term that some people who identify as LGBTQ don’t like because it was once widely used as a slur, and of course the original meaning of the word is “strange.” However, some folks love this term. It’s a little bit playful, and as an umbrella term, it’s much less of a mouthful than LGBTQ+...but also, it’s because a lot of us don’t neatly fit into the sexual or gender categories listed in LGBTQIA, so identifying as “queer” is a quick way of saying “I’m something other than heterosexual and/or cisgender” without having to fully define your gender or sexual orientation.